What next in China's Wukan stand-off?

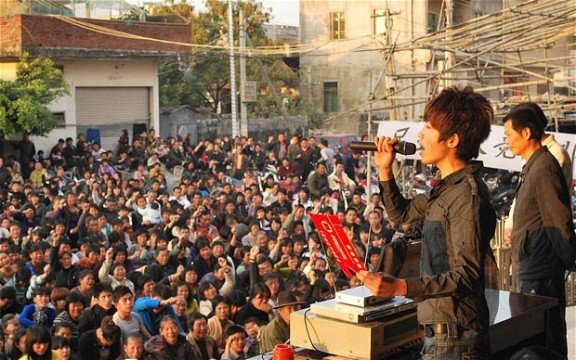

A stand-off between a group of determined villagers and local government representatives in China’s southern province of Guangdong is currently adding to the formidable workload of country’s indefatigable army of Internet censors.The name of Wukan is being ‘scrubbed’ from the Chinese Internet after the plight of the village’s inhabitants became a cause celebre among Chinese netizens for their stubborn protest against land seizures by corrupt local officials.Simmering since September, the story received international attention when it was revealed that one of the village negotiators, whom the authorities suspected of being a ringleader, died in police custody after being snatched on December 9.While events are being reported outside China, the country’s censors have put a lid on the story within, shutting a temporary window when videos and photographs of the village protest and the attempted police crackdown were easily shared among China’s Internet users. The village has been sealed off by a police cordon that is preventing food and supplies from crossing to the villagers.The good news is that negotiators on both sides appear to be reaching a rapprochement of sorts with the authorities trying to calm the situation after a forceful crackdown using hundreds of police failed dismally. Here are the latest developments from Radio Free Asia and the China Media Project.The story of Wukan is the latest of an estimated 150 thousand protests that occur in China each year. By and large, the causes of the protests are dispossession, exploitation and corruption at the hands of government officials in cahoots with powerful business interests.The one big difference with Wukan is the sizeable corps of foreign correspondents that embedded themselves among the villagers. Journalists from the Daily Telegraph, McLatchy Newspapers, the New York Times, NPR Radio and others have been reporting from the village and creating an extra headache for the officials who have been trying to cover up the story and resolve it quickly. As this New York Times story says, another critical factor in the heightened level of coverage is the number of Hong Kong news media covering the issue.Malcolm Moore of The Daily Telegraph is the foreign correspondent who provided the first reports of the village rebellion in the overseas media although the villagers themselves are keen to avoid the issue being reported as an uprising or rebellion. In what can only be described as a tactical move, they are keen to underline that their dispute is with the local officials and their appeal is to central government for justice.But while the news about Wukan has been getting out, it is no longer getting in. Wukan has ‘disappeared’ from China’s social web, except when it appears in news items generated by state news media sources.According to Reporters Without Borders, Wukan is now blocked on search engines and “hot tweets” are being closely monitored.The BBC reports that users of China’s most popular micro-blogging site, Sina Weibo, can no longer find results for Wukan in searches.Radio Free Asia says a video showing thousands of villagers gathered in protest was quickly removed after being posted on the Sina and Tencent. Here is a video compilation of events, edited by Charles Custer at China Geeks.Blocking and censoring the topics that the government considers a threat to its stated aim of maintaining social harmony is one part of the equation. David Bandurski of the China Media Project says the Wukan case is also notable for the government’s more sophisticated approach to “channelling public opinion” – spin, by another name.

A stand-off between a group of determined villagers and local government representatives in China’s southern province of Guangdong is currently adding to the formidable workload of country’s indefatigable army of Internet censors.The name of Wukan is being ‘scrubbed’ from the Chinese Internet after the plight of the village’s inhabitants became a cause celebre among Chinese netizens for their stubborn protest against land seizures by corrupt local officials.Simmering since September, the story received international attention when it was revealed that one of the village negotiators, whom the authorities suspected of being a ringleader, died in police custody after being snatched on December 9.While events are being reported outside China, the country’s censors have put a lid on the story within, shutting a temporary window when videos and photographs of the village protest and the attempted police crackdown were easily shared among China’s Internet users. The village has been sealed off by a police cordon that is preventing food and supplies from crossing to the villagers.The good news is that negotiators on both sides appear to be reaching a rapprochement of sorts with the authorities trying to calm the situation after a forceful crackdown using hundreds of police failed dismally. Here are the latest developments from Radio Free Asia and the China Media Project.The story of Wukan is the latest of an estimated 150 thousand protests that occur in China each year. By and large, the causes of the protests are dispossession, exploitation and corruption at the hands of government officials in cahoots with powerful business interests.The one big difference with Wukan is the sizeable corps of foreign correspondents that embedded themselves among the villagers. Journalists from the Daily Telegraph, McLatchy Newspapers, the New York Times, NPR Radio and others have been reporting from the village and creating an extra headache for the officials who have been trying to cover up the story and resolve it quickly. As this New York Times story says, another critical factor in the heightened level of coverage is the number of Hong Kong news media covering the issue.Malcolm Moore of The Daily Telegraph is the foreign correspondent who provided the first reports of the village rebellion in the overseas media although the villagers themselves are keen to avoid the issue being reported as an uprising or rebellion. In what can only be described as a tactical move, they are keen to underline that their dispute is with the local officials and their appeal is to central government for justice.But while the news about Wukan has been getting out, it is no longer getting in. Wukan has ‘disappeared’ from China’s social web, except when it appears in news items generated by state news media sources.According to Reporters Without Borders, Wukan is now blocked on search engines and “hot tweets” are being closely monitored.The BBC reports that users of China’s most popular micro-blogging site, Sina Weibo, can no longer find results for Wukan in searches.Radio Free Asia says a video showing thousands of villagers gathered in protest was quickly removed after being posted on the Sina and Tencent. Here is a video compilation of events, edited by Charles Custer at China Geeks.Blocking and censoring the topics that the government considers a threat to its stated aim of maintaining social harmony is one part of the equation. David Bandurski of the China Media Project says the Wukan case is also notable for the government’s more sophisticated approach to “channelling public opinion” – spin, by another name.

The emphasis on “channelling public opinion” so prevalent in media policy these last few years — what we have at CMP termed “Control 2.0″ — essentially comes down to finding more effective ways of spinning these public opinion crises, managing dangerous stories in the era of real-time interactive information.

Bandurski, an American who speaks and writes Chinese, says control of the Wukan story has been ‘robust’. When he posted a Chinese-language summary of a story by Malcolm Moore on Sina Weibo, it was quarantined in less than a minute.

Clearly Wukan is an object lesson in the dangers of runaway corruption at the local level in China. But it is also, unfortunately, shaping up as a test case in how the government is experimenting with new strategies to shape news coverage on sensitive incidents and issues.

The rapid growth of Internet users and mobile communications is deeply concerning for China’s Communist Party rulers and the speed and breadth by which a protest can escalate online presents a clear and present challenge to the Party’s hold on power. The real time multiplier effect that makes the Internet so formidable can give rise to hundreds of Wukans with no end in sight. A localised event can transform into national issue in an Internet blink.The social marketing agency, Resonance China, says China’s web is a very personal space that allow otherwise economically and politically restricted Chinese a sense of freedom.

The drive to express online is a central motivation for the Chinese. Due to China’s strong censorship and control of traditional media, the internet becomes a major destination to receive balanced views, see how others think and react to events, and share and express one’s individuality.

We all know that personal space and political space mingle inextricably on the web. The balance of power between Chinese netizens and the machinery of censorship shifts constantly as the government attempts to imprint its sense of order on what it sees as a lawless and threatening frontier. But as the aggrieved residents of Wukan have been trying to tell the world, the attempts by the authorities to enforce the law don’t mean anything if there is no justice. That's a point that seems lost on at least one important actor in the events that led to one village in China losing its faith in the system.